Bohemian Behemoth

I’m a member of a Facebook group called “the Mandocello Enthusiast,” and in a recent discussion thread, a member named Yvonne (who plays in the Dayton Mandolin Orchestra) commented on how much she loved the mandocello that she’d been playing of late, a Stahl/Larson Bros.model from the early part of the last century, and she posted some pictures of it and a similar one. It was teardrop shaped, , and with a folded spruce top that mystified me at first as to its construction. After sleeping on it, I woke up understanding how it was done, so never underestimate the value of dreams.

This is the type of top used on most bowlback mandolins, and I immediately understood its advantage. The crease, which is created by cutting a straight groove across the grain on the underside of the top, and bending it under steam, adds rigidity to the top in the same way as when you fold anything, like a cardboard box. The area behind the bridge to the tailpiece, about a third of the top, needs minimal bracing as a result, which creates a separate soundboard in effect , for the lower register, and I could imagine how this effect might be used to great advantage, particularly on the cello and octave mandolin.

So I determined to make a similar design, which has yielded this mandocello, which I’m calling the “Bohemian.”

The name is derived from two converging ideas. First, Yvonne had mentioned that she lived in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and I have a history with that delightful little hamlet that brought back a flood of memories. Home of Antioch College, it’s located about 7 miles from the town in which I lived for my high school years in the late 1960’s. The contrast could not have been greater to the Air Force town, Fairborn, in which I lived. Antioch was so radical at that time that it made Berkeley and Brandeis look like William and Mary. At a time when Student Power was gaining ground, not just as a demand of student protest, but as an educational philosophy, at Antioch, that war was over.

The Little Art Theater in Yellow Springs, which is still in operation, seats a capacity crowd of about 60 as I recall, and I took in a lot of great movies that I might not have seen otherwise, Fellini, Wertmuller, early John Waters (years before Pink Flamingos) and on one occasion, a filmed stage play of The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum at Chareton Under the Direction of the Marqquis de Sade.

The plot was basically that in the course of performing this play about a patriot of the French Revolution, the inmate/actors become so passionate that they overthrow the director of the asylum. It foretold the fate of Antioch, in a way, because the inmates were running the asylum at Antioch. Having become a magnet for young people seeking social change, it was unfortunately located in an idyllic village far from the problems of modern society. This resulted in a pervasive paranoia, I think, and a game of radical one-upsmanship ensued.

But as a young radical aspirant, it seemed like heaven to me, and as a 17 year old, I spent much time on the streets there and wandering the trails of nearby John Bryant State Park.

On a warm late spring evening in 1970, I sat on the grass in a park on the edge of campus and listened to Canned Heat and Van Morrison perform great sets. In between acts, someone had dreamed up a stunt involving a huge plexiglass half-sphere with 20 gallons of jello in it, and sought volunteers (female, of course) who would jump in and slide around. Not only were there no takers, but a chant started, and quickly took hold of the crowd: “F—Warner Brothers, F—Warner Brothers,” a reaction to the Woodstock movie that was seen by many as exploitative of the “Movement.” I got a kick out of it, but also began to see the students at Antioch as being kind of pathetic. There was, after all, no film crew on hand. When I went to Temple University in North Philadelphia the next fall, it was abundantly clear to me that the least of our problems was Warner Brothers.

As a result of the personalities and lifestyle choices that would befit a faculty that was amenable to such a curriculum and campus, the town had what one would call a “Bohemian” atmosphere, and the small businesses that supported the student population were not Kinko’s and Starbucks, they were headshops, alternative bookstores and the art house theater. At one such bookstore I would regularly pick up a copy of the L.A. Free Press, or the Voice (which was less mainstream in those days). The same store is where I bought my first John Fahey record (on Takoma, of course) which I still have and play to this day. It’s also where my Dad sold his first dulcimer, the first of many hundreds he would end up selling all over the country.

So “Bohemian seems to suit an instrument whose origin, in an obtuse way, lies in Yellow Springs.

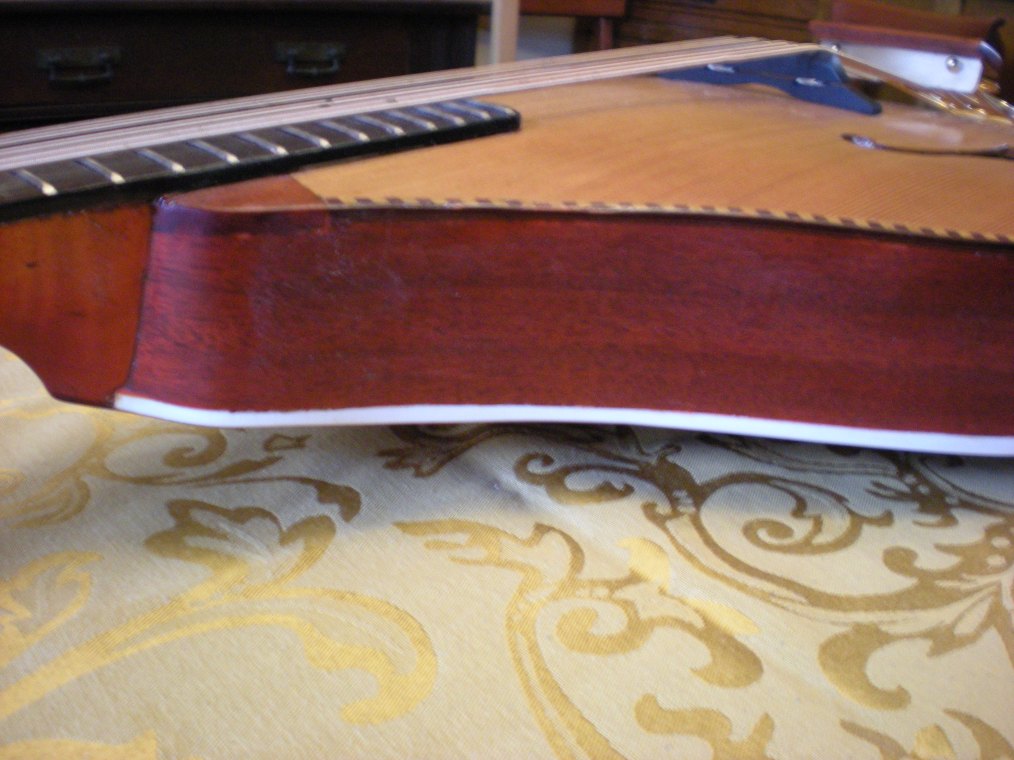

I made an unusual back for this. I was inspired to visually mimic the bowl back that one might expect to see on such an instrument. I glued up solid triangles of padauk, with strips of maple in between, then carved an arched shape out of the resulting slab of wood. The effect was visually pleasing, and while the inherent weight of padauk added a pound or two to the instrument, it is highly resonant and sonically reflective, making it an effective back for this.

After completing it, I ran across an article about a style of mandolin making in parts of Germany which uses this exact idea. So, Bohemian.

Here’s a video of the amazing Joe Brent playing it:

Joe’s very entertaining tumbler of mandolin reviews is here.

Sometimes you fall in love with an instrument as you’re building it. In fact, I usually do, which can make it difficult to be objective once it’s all done. So I’ll leave it to others to judge it. But my personal assessment is that, as Yvonne had suggested about hers, this cello has remarkable clarity and tone across the range that it plays, thunderous lows, and sweet highs. I’m almost finished with an octave mandolin version of this, and I can’t wait to hear that…